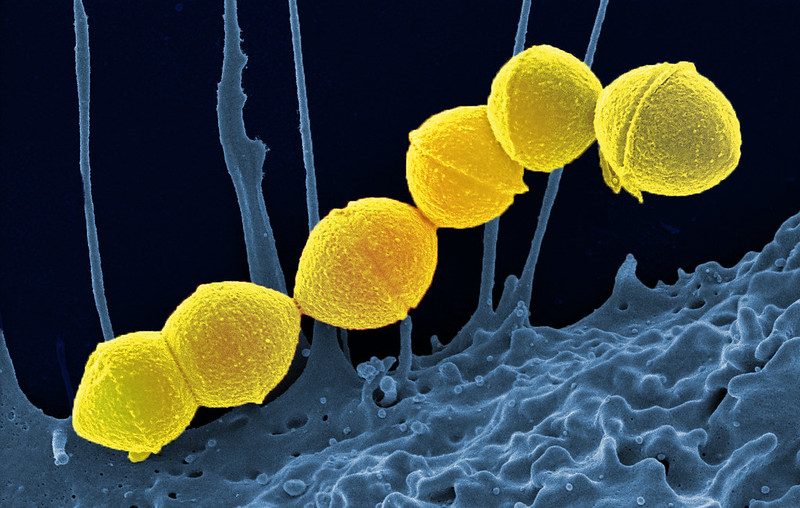

Group A streptococcus (GAS), also referred to as Strep A is a common bacterium. Lots of us carry it in our throats and on our skin and it doesn’t always result in illness. However, GAS does cause a number of infections, some mild and some more serious.

The most serious infections linked to GAS come from invasive group A strep, known as iGAS.

These infections are caused by the bacteria getting into parts of the body where it is not normally found, such as the lungs or bloodstream. In rare cases an iGAS infection can be fatal.

Whilst iGAS infections are still uncommon, there has been an increase in cases this year, particularly in children under 10 and sadly, a small number of deaths.

This blog explains more about GAS and the infections it can cause, as well as how it is spread and what to look out for when your child is unwell.

How is it spread?

GAS is spread by close contact with an infected person and can be passed on through coughs and sneezes or from a wound.

Some people can have the bacteria present in their body without feeling unwell or showing any symptoms of infections and while they can pass it on, the risk of spread is much greater when a person is unwell.

Which infections does GAS cause?

GAS causes infections in the skin, soft tissue and respiratory tract. It’s responsible for infections such as tonsillitis, pharyngitis, scarlet fever, impetigo and cellulitis among others.

While infections like these can be unpleasant, they rarely become serious. When treated with antibiotics, an unwell person with a mild illness like tonsilitis stops being contagious around 24 hours after starting their medication.

We are currently seeing high numbers of scarlet fever cases.

The first signs of scarlet fever can be flu-like symptoms, including a high temperature, a sore throat and swollen neck glands (a large lump on the side of your neck).

A rash appears 12 to 48 hours later. It looks looks like small, raised bumps and starts on the chest and tummy, then spreads. The rash makes your skin feel rough, like sandpaper. The rash will be less visible on darker skin but will still feel like sandpaper. More information on scarlet fever can be found on the NHS website, including photos.

What is invasive group A strep?

The most serious infections linked to GAS come from invasive group A strep, known as iGAS.

This can happen when a person has sores or open wounds that allow the bacteria to get into the tissue, breaches in their respiratory tract after a viral illness, or in a person who has a health condition that decreases their immunity to infection. When the immune system is compromised, a person is more vulnerable to invasive disease.

Which infections does invasive group A strep cause?

Necrotising fasciitis, necrotising pneumonia and Streptococcal Toxic Shock Syndrome are some of the most severe but rare forms of invasive group A strep.

What is being done to investigate the rise in cases in children?

Investigations are underway following reports of an increase in lower respiratory tract Group A Strep infections in children over the past few weeks, which have caused severe illness.

Currently, there is no evidence that a new strain is circulating. The increase is most likely related to high amounts of circulating bacteria.

It isn’t possible to say for certain what is causing higher than usual rates of these infections. There is likely a combination of factors, including increased social mixing compared to the previous years as well as increases in other respiratory viruses.

What should parents look out for?

It’s always concerning when a child is unwell. GAS infections cause various symptoms such as sore throat, fever, chills and muscle aches.

As a parent, if you feel that your child seems seriously unwell, you should trust your own judgement.

Contact NHS 111 or your GP if:

- your child is getting worse

- your child is feeding or eating much less than normal

- your child has had a dry nappy for 12 hours or more or shows other signs of dehydration

- your baby is under 3 months and has a temperature of 38C, or is 3 to 6 months and has a temperature of 39C or higher

- your baby feels hotter than usual when you touch their back or chest, or feels sweaty

- your child is very tired or irritable

Call 999 or go to A&E if:

- your child is having difficulty breathing – you may notice grunting noises or their tummy sucking under their ribs

- there are pauses when your child breathes

- your child’s skin, tongue or lips are blue

- your child is floppy and will not wake up or stay awake

What are schools being asked to do?

Schools are being asked to follow the usual outbreak management processes as set out in our guidance if an outbreak of scarlet fever is identified. An ‘outbreak’ is defined as 2 or more probable or confirmed cases attending the same school, nursery or other childcare setting within 10 days of each other.

Schools and nurseries should contact their local Health Protection Team if:

- You have one or more cases of chickenpox or flu in the class that has scarlet fever at the same time. This is because infection with scarlet fever and either chickenpox or flu at the same time can result in more serious illness.

- You are experiencing an outbreak of scarlet fever in a setting or class that provides care or education to children who are clinically vulnerable.

- The outbreak continues for over 2 weeks, despite taking steps to control it.

- Any child or staff member is admitted to hospital with any Group A Strep (GAS) infection (or there is a death).

Schools where outbreaks occur are additionally advised to:

- Make sure that all children and employees that are ill go home and don’t return until they are well.

- Tell parents and visitors about the cases of illness.

- Remind employees to wash their hands throughout the day. Hand washing needs to be done after changing nappies and helping children use the toilet.

- Make sure that all cuts, scrapes and wounds are cleaned and covered. This also applies to bites.

- Carry out regular cleaning throughout the day, especially hand contact surfaces – this is covered in Managing Outbreaks and Incidents. Advice may also be given to increase cleaning of areas with particular attention to hand touch surfaces that can be easily contaminated such as door handles, toilet flushes and taps and communal touch areas. These should ideally be cleaned using a disinfectant.

- Consider stopping messy play, removing hard to clean soft toys, not going on visits outside of your setting and not allowing children to share drinks

- Once cases have stopped (no new cases or illness for 10 days), do a full cleaning of buildings (including toys, carpets etc)

Who needs to take antibiotics?

Antibiotics are not routinely recommended as a preventative treatment and should only be taken in confirmed cases of scarlet fever or another GAS infection, or in certain circumstances where Health Protection Teams recommend their wider use.

If there are cases identified in a child’s class, any child showing symptoms should be assessed by a doctor/by their GP and will be prescribed antibiotics if needed. Children are not infectious after 24 hours on treatment and can return to school once they’re feeling well enough after this period.

Are children with chickenpox more vulnerable to iGas?

Children who have had chickenpox recently are more likely to develop serious forms of Group A Strep infection, although this remains very uncommon. The chickenpox rash can make it easier for Group A Strep to get into the body, which can lead to invasive infection. If a child has chickenpox – or has had it in the last 2 weeks – parents should remain vigilant for symptoms such as a persistent high fever, cellulitis (skin infection) and arthritis (joint pain and swelling). If you are concerned for any reason please seek medical assistance immediately.

How can we stop infections from spreading?

Good hand and respiratory hygiene are important for stopping the spread of many bugs. By teaching your child how to wash their hands properly with soap and warm water for 20 seconds, using a tissue to catch coughs and sneezes, and keeping away from others when feeling unwell, they will be able to reduce the risk of picking up, or spreading, infections.